|

|

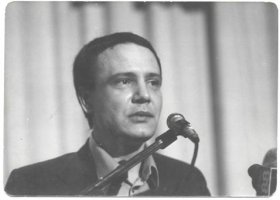

Alexander Sergeyevich Yessenin-Volpin, 1970. |

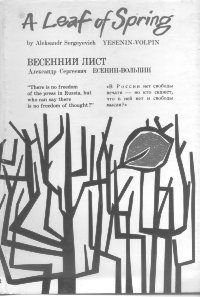

On July 1, 1959 a young Soviet poet, mathematician and philosopher was asked to write an essay on his ideas, so that an American traveler could carry it to the West. The task was very urgent: it had to be completed in a few hours. It was not, also, without danger. Contacts with foreigners were strictly forbidden, even at this late stage of Khrushchev's "thaw." True enough, a few weeks later the author's accomplishes in these "illegal acts" were arrested for "espionage in favor of the West" and for "disseminating state secrets."(1) The author was also incarcerated. But, in a practice that he knew well — and which would become infamous later — he was not confined in a prison cell. He was committed in a mental hospital. By arresting him, though, his persecutors had made a grave mistake: Praeger, the publishers abroad, had agreed that in case of his arrest they would proceed and publish the manuscript, immediately. As a result of this chain of events, in 1961, a small book appeared in the West, containing an assortment of poems and a thirty-page long philosophical essay, under the collective title "A Leaf of Spring,"(2) It brought to the light the poems and the philosophical theories of Alexander Sergeievich Yessenin-Volpin, a highly original thinker. Today, with the hindsight of almost half a century of stupendous events in the history of the Soviet Union, we can safely say that the appearance of this slim tome was much more important than its short length indicated: it can easily serve as the opening act of the last phase of Soviet history. And the "Free Philosophical Treatise," the clandestine essay that brought his author confinement in a mental hospital, can easily be considered as the founding text of what, more than fifteen years later, came to be called the "dissident movement."

Sergei Esenin

Sergei Esenin |

Alexander Yessenin-Volpin is one more proof that the Soviet theory of familial collective responsibility had at least some merit. The son of the famous Soviet poet Sergei Esenin and Nadhezda Volpin, Alexander Yessenin-Volpin was born in 1924, and grew up with his mother and grandfather in St. Petersburg (Leningrad.) His father, whose flamboyant character, fiery poetry and good looks made him a legend in his time, saw him only once, and soon met a tragic end: On December 28, 1925 he committed suicide in the hotel room where he and a previous wife, the famous American dancer Isadora Duncan, had spent their honeymoon. |  Nadezhda Volpin

Nadezhda Volpin |

The young poet's loss was one that was deeply felt by his female compatriots who, almost a century later, still decorate his grave with hearts, flowers and pictures. Sergei Yessenin was considered a revolutionary poet and Trotsky composed a splendid eulogy on his death.(3) But Sergei Esenin's Bolshevik zeal seems to have subsided towards the end, and the Soviet regime never forgave him for this, a fact that became obvious when his older son, Yuri, was executed for threatening the life of Stalin — allegedly, he had exclaimed to an acquaintance that Lenin and Stalin should have been killed and the Kremlin blown up. As Yessenin-Volpin says today, "Words, nothing more. And for such words a man could be shot."

|

Nadezhda Volpin and young Alexander, 1928. |

In many ways, then, it was almost inevitable that, at some point, Alexander would try his hand in poetry and that, probably, some of his poems would reflect these bitter events. What was completely unpredictable was that he would also become a brilliant thinker and that his true calling would prove not to be poetry but mathematical logic, a field in which he would find the inspiration to create political theories that would eventually bring the decomposition of the Soviet system itself.

To understand the path that Yessenin-Volpin's ideas followed, we have to start from his very early years. Both his father and his mother hailed from non-mainstream cultures. His father was born in a family of Russian Orthodox Old Believers, a group that had been persecuted harshly for its adherence to the old Russian liturgical rituals that the established Church had rejected. His mother came from a Jewish upper-middle class family of the old Moscow intelligentsia.

As he recounts his story,

"I was a mixture … I was born in Leningrad [in] 1924 and lived there my first eight years with my mother. But then my mother rotated in Moscow. Since [then] I have lived in Moscow — till emigration."

Nadezhda Volpin, was a literary figure in her own right. She was a literary translator and author, and her reminisces of Osip Mandelshtam and his wife are one of the very few first-hand accounts we have of this great poet, whose life ended in the Gulag, in 1938. It was she who ensured that young Alexander would have the opportunity to access the masterpieces of the world intellectual heritage, in the original. "Before the war my mother had decided [that he would study the major European languages.] In the school [it] was German, [it] was nothing. But I had a special German lady. And the last years I studied myself, ... French. My mother helped me with a French teacher and I was impressed by French poetry." |

Nadezhda Volpin, 1980. |

If poetry seems, naturally, to have interested the young student, his interest in Logic and the Law had a different source:

"My grandfather was a lawyer. And he left me some juridical books. I could read them.... I was about fifteen or sixteen when I said that I do not recognize whatever they tell me — only things on issues I shall solve by my own training. After having set to compare two or three incompatible sentences [I said] 'Yesterday you said other.' Every schoolboy can [do this.] It is clear. I was the schoolboy who persisted. That is a matter of character."

He was not drafted to the army on a diagnosis of schizophrenia, that was made without an examination. "They had some psychiatrists and, strange, they had seen I had schizophrenia. Schizophrenia without any examination! Even with a real schizophrenic that would take an examination."

But for him the diagnosis was a blessing in disguise — he avoided the War and was able to study:

"... I came to the Mathematical Dept. — Mechanico-Mathematical Dept. (in Moscow) in 1941, when I was 17... I was impressed with the works of Bertrand Russell and ... also others, like Nitze. ... Several philosophers. Of course Kant. I read also ancient philosophy. But in the modern time [I concentrated] on rational thought ... Now, in 19th century, Boole. But Bertrand Russel was the most famous. I was impressed by his paradox in Set Theory. ... I studied his collected results. But [I did not start] ...immediately with the paradoxes — one has to be elevated, to grow up to this. That took years. ... I started with the topologists and my first thesis, Ph.D in American terms, it was in '49 — it was on compact spaces. But that was really soon interrupted because on July 21st of the year 1949 I was imprisoned. I was 25 years old. [I was arrested] Because I wrote some verses.

... That was the first time I had prison experience (he laughs.) How to deal with the prosecutor in order not to become a traitor to myself. They tried to. They tried to decompose me. [I learned] How to go around, around. The prosecutor said that 'For us your mathematical experience is nothing.' [He said that] Maybe I could just … work as a mathematician and then [it would be] o.k. But not to write verses."

Instead of imprisoning him, though, the authorities committed him to a mental institution — probably because a further persecution of members of the Esenin family would have created unwanted questions. As Yessenin-Volpin says "They had fulfilled their quota with the Esenin family."

"... I had to spend only a year at the mental institution. Here [In Russia] there is a danger that they will keep you there indefinitely. Six months is given unnecessarily {without obvious cause}. Every six months there is a commission and ... you [have to] wait for the commission. They asked what did I think about it now [his offence] and I said, 'Why, with my illness you know better than me.' And I ... continued to write verses — already in prison but more in Karaganda."

In Karaganda, Kazakhstan, he was exiled after his incarceration and there he worked as a mathematician (his "mental illness" having been forgotten, of course.) Freed from the mental institution, Yessenin remembers his exile in a positive light:

"Two years and a half I spent in Karaganda. It could have been a lot with these people. [In Karaganda] I was free. I could vote. I could only not leave the place. ... And then I started to work. I had studied, I had books, my works had been published. I became a scientist of mathematics in Karaganda. I am a Kazakh."

An important part of his new education was on legal matters, a knowledge that would prove invaluable, a few years later.

"... When I came to Karaganda ... I went to the local libraries and read the Procedural Code. I read and understood many things which people have to understand — but they never read Procedural Code."

And then Stalin died.

"... After Stalin's funeral there was an amnesty. I didn't have to spend (serve) all my years [in exile,] only half of that and then return ... to Moscow. In Moscow, of course, we all suffered because of the compulsory ideology of the so-called dialectical materialism — which actually did not exist. ... You could say that you don't believe, but that could cost you your job and so on. ... I worked only on some accidental works, but in Russia you can survive that way, and I lived. I visited the University, but I could not work on [the] grounds that, since '56, I started to develop my own direction on mathematics. [Mathematics] starts with the principle of the uniqueness of the Natural Number series, Dir 1 and so on. And I asked, 'What it means 'and so on?' Maybe there can be a different Natural Number series, then the whole mathematics is revised.'"

|

Aleander Yessenin-Volpin speaks at a seminar on Mathematical Logic to the faculty of the Mechanico-Mathematical Department of the University of Moscow. In attendance are A.A. Markov, V.A. Uspensky, S. N. Adyan, B.A. Trachtenbrot, Y. A. Shihanovich. Early 1950's. |

"I decided to do just that [ To revise Mathematics.] They didn't want to listen, to understand. 'You are going to spend your life.' 'I am ready to spend my life. That is after all my own business and decision.' ... I could not expect to be paid even a kopeck for that. I needed some job, I did some reviews, theoretically I was occupied to do reading, as much as I could. Also in my field I corresponded, of course. I just needed a person who can read. I could read several languages, main European languages. So I decided to continue."

Yessenin-Volpin was determined to follow his own intellectual path. Prison had not curbed his opposition to the regime and he wanted to publish his poetry and his philosophical work:

"I had an old decision finally to publish that what I am writing. I thought misconceived the communist ideology. I am not a materialist, too. But not that I am against a government. Always we will have a government. ... This government. ... Another one. But, there is repression. Stalin is already dead. Even before he died I decided that sometimes I will emigrate, or, if that is impossible, just to mail [my works] overseas for ... publication. And then ... let them do whatever they want. It is already published. I said that: 'Disprove me, but your prisons are not for me [will not defeat me].'"

Eventually he succeeded in publishing the "Leaf of Spring" — and, despite Khruschev's professed "thaw," he was immediately arrested again:

"... That was the second time I was imprisoned. ... Five times I was put

in mental institutions. I said 'Keep me there as far as you will, but I will

remain as I am.' ... They said 'You have experience, how could you commit

such a thing?' I said 'How could they commit the same things as then? [As

in Stalin's time] I thought that it is impossible in our time to be in prison.'

'And what do you think about that now?' 'And now I think it is possible.'"

(he laughs.)

| The title "A Leaf of Spring," that Praeger gave Alexander Yessenin-Volpin's seminal collection of works, proved to be prophetic. Exactly thirty years after its appearance, the Berlin Wall collapsed. |

|

It was during this interrogation that, for the first time, Yessenin-Volpin started developing the response to his oppressors that he would later perfect:

"... This time, though, I had experience. I knew how not to answer the questions of my prosecutor. They said 'So you have talked' [with the other accused]- but there was no crime, and [I said] 'You have nothing to ask me about. I refuse to answer your questions. ... Just not to have a faith is not an argument in order to keep you in a mental institution'"

They asked him if he didn't know that there were other cases like his in mental institutions. He said "Yes, I believe there are such cases in the mental institution. Yes, I believe in your capacity to keep me there." They asked "Do you wish to be important?" He answered: "Do you want to prove me right?"

He laughs " ... I could prove to be more consistent than themselves, but I am a logician. And logic is indeed the use of the signs."

These sparrings with his interrogators may appear simple semantic altercations, on paper — but they would later prove to be the blueprints for the weapons of a truly revolutionary political movement. A little later Yessenin-Volpin makes another major political invention:

"...There was a case in 1963-1964. I was in the institution, some journalist Shatunovsky wrote a paper about myself, he called me a villain, and again a villain, and he called me a liar. I called him to trial. And there was a trial. And they expelled the public, which was absolutely illegal. I said 'But...' Of course they understood before I could say any word, but they understood what I would do next and they [had] nobody. [I thought] 'But their whole trial system is based on such distortion of the law in their favor, behind closed doors. That's what they need! Well, let the doors be open! I need their doors to be open!'"

Yessenin-Volpin demands, for the first time in Soviet history "Glasnost." (Author's note: Reviewing my notes Yessenin-Volpin put a questionmark over the word "first.")

"I used that word because that word is the word used by the Procedural Code. They have another word for openness. … That is about the same. About the state of openness. [I thought] I will say to everybody about openness! (he laughs) I just took this word."

It was this combination of the demand for Glasnost and the insistence that Soviet authorities observe Soviet laws that constituted the revolutionary approach to the Soviet political problem that came to be known under a number of different titles, all of them pertaining to its central demand: Legality, the Legality strategy, the Legality methods. It is even common that authors refer to the new approach in more diffuse terms: as a new "Human Rights language," for example, as does Alexander Gribanov. (4)

And yet, all these names overlook the most critical component of

Yessenin-Volpin's political invention: Yessenin-Volpin's political work had

its foundation in his mathematical and philosophical research,

and followed closely the tenets of the cybernetic paradigm. Accordingly,

the strategy he proposed should rightfully be called the "Legality

Program," a term that, conforms perfectly to historical facts and which

we will analyze elsewhere.

|

Alexander Yessenin-Volpin with a group of other academics. Among them, V. A. Smirnov, V. F. Asmys, Y. A. Gastev, A. A. Zinoviev, I. S. Narsky and others. Kiev, 1965 |

In the fall of 1965, the dissident movement had for the first time the opportunity to test the effectiveness of the Legality Program:

"... Then there was a case, a Russian writer called Avram Tertz, his real name was Sinyavsky, and his friend Daniel. ... In September 65 in mid September, September 18, Sinyavsky [was] arrested ... Three days later I heard that he [was] the same as Avraam Tertz. [I thought] 'O.K., they will make this trial. We have to demand publicity of the trial. The trials must be public.'"

Now, Yessenin-Volpin's ideas are put into action.

"... I already knew [Vladimir] Bukovsky (5) and

other people, they had been looking for such activity and suggested: 'Let

us demand the opening of their trial, Sinyavsky and Daniel. Maybe we cannot

succeed in their liberation — we would prefer that — but let the

trials be open. In this case, as in other cases, as it must be by Constitution.

There is no state secrecy in that [their case.]'

Some people, most people, ironized [were ironic.] That it was intellectual

stupidity. One man ... he understood the idea, he was able to understand

the truth: We simply had been afraid to work actively for a case that would

bring nothing immediately. [I said] 'Not immediately, maybe for generations.'

I understood that 'immediately,' but for generations to come that was a start.

We do something noticeable. Maybe the trial will not be open — and indeed

we were tried instead, though for ... [demonstrating] and demanding for the

Constitution."

"And this guy suggested to organize it, just as the day was approaching of the Day of Soviet Constitution, December the 5th [1965] of Stalin's Constitution. And we have chosen that day, me and this Nikolsky — Valerii Alekseyevich Nikolsky, unfortunately he died in mid '70's, he was a young physicist. ... And there was a "meeting of publicity" [Glasnost meeting] as I called it, people ... demonstrated to our three slogans, a hundred people. ... On the Pushkin Square. Close to the monument. We chose this place with Nikolsky because when we thought ... [about] which place to be chosen for that, [we wanted] anywhere with movement [traffic.] In Pushkin Square is the newspaper Izvestia, officially the first ... paper in the orders of the Bolsheviks — officially that was their paper — ... and we ... organized the publicity [meeting] before ... [the entrance of] the building, in the lower section, just in the street."

|

Vladimir Bukovsky, and a small group of young Moscovites, converted Yessenin-Volpin's philosophical ideas to political reality — in the face of severe persecutions. Bukovsky was arrested a few hours before the Pushkin Square demonstration and was incarcerated intermitently in prisons and mental institutions for the rest of his Soviet life. In 1976 the Soviet regime exchanged him with the Chilean Communist leader Louis Corvallan — a tacit acceptance by the Soviet regime of Bukovsky's important political stature. In the picture, Bukovsky is seen giving a speech,in Germany, in 1977, shortly after his release from Soviet prison. |

As could be expected, the KGB was also very intrested in Yessenin-Volpin's ideas and the Pushkin Square experiment. The demonstration was violently broken up by KGB agents, as soon as it started, and the organizers were beaten up and arrested. What was unexpected to all, except, possibly, to Yessenin-Volpin, was what came next: It became apparent that the Legality Program could defeat the Soviet regime's methods, after all:

"Then I was detained. They put me I don't know what it was, not a prison, some of their KGB Soviet detention centers. There, met me a person, that called himself a representative of the Moscow Soviet. 'Trial? Why do you want that? You know who is organizing the demonstrations in our country. [the Communist Party.] You ask for people to respect Constitution.' (We had asked for publicity for such and such and we added: 'Respect the Soviet Constitution.' ) I said, 'Is there a crime to respect the Soviet Constitution? I will not say respect — [I will say] observe. But other people have said 'respect.' 'Are there people,' they asked me, 'who don't respect the Soviet Constitution?' 'It seems to me there are.' 'WHO?' 'Just today, there is the day of the Soviet Constitution, we ask in this day for the respect of the Soviet Constitution, and we are detained. Our slogans were taken away, and the one for publicity was torn. I think those people [who did this] don't respect the Soviet Constitution.' Silence. And then 'Let them go.'"

The philosopher understood, also, that Glasnost could be equally effective if it was demanded retroactively — because this would put into question the historical foundations of the regime:

"... There was Peter Yakir,(6) his house, people meeting there. And then there was another plan for another demonstration, on March, for the death of Stalin, more emotional. 'Publicity of trial' was not emotional enough. I said 'Enough of emotions we have in our life, we have now to be liberated of emotions, rather than [have] them ... be brought forth. But if you want it on Stalin, you also have [the] right.' I proposed the slogan: 'The publicity is needed not only in trials.' They [the KGB] could say they knew everything, but they surrounded my home so that I could not go out until then. [He laughs] This time that [the demonstration] was on the Red Square. That was an attempt to organize publicity — Glasnost — twenty years before Gorbachev."

Alexander Yessenin-Volpin formulated also the exact political argument that the dissidents should adopt: Dissidents were not against the Soviet system per-se: They were defending Soviet legality, which the regime itself was violating by demanding obedience to an undefined "Soviet ethos" — when, in fact, it was demanding an unconstitutional obedience to its political ideas:

"... I said [to the other dissidents] : 'Do know, we have actually nothing against genuine Soviet power. It simply doesn't exist.' 'And [writen laws?]' 'Eh, that is not the best form of legislation, but we need that ... to get back. Because that we can demand.' That was what they claimed to be: 'Oh, I am not an anti-Soviet man anymore.' And they were not, because then simply there was confusion about Soviet-communism. That was not my confusion — the whole country was confused. [He laughs] And [we said] 'Yes, we need Soviet Constitution, Soviet Power, but the first enemies of the Soviet Power are some persons in the Central Committee. They are not Soviets. They have usurped the Soviet Power. And they have destroyed it.'"

He had studied Soviet history and had found that:

"It is interesting especially with regards what is Soviet, what is communistic. These are two different concepts and by the end of the Soviet Union [it was obvious ] that [this] was the case. Gorbachev [vs.] Yeltsin. In 1991 the Communist Party was forbidden and there was a Soviet Union without the Communistic Party. (laughs) But the Soviet Government did exist. How long it could exist? Just four months. But still it could."

What the logician, Yessenin-Volpin, had seen was that the major breach in the Soviet State's structure was the dichotomy between Party and State. And his highly original political analysis had made it clear that it was this fault line that made the Soviet regime vulnerable — because the Soviet State had never been constitutionally abolished or assimilated to the Communist Party structure:

"... not officially. Only they used that form [the State] just as a mask."

Tactically, the time was also ripe for a more aggressive attack on the Soviet system:

"That year (1965) Khrushchev had been deposed a year ago and Brezhnev had not been strong enough yet, so they committed a serious mistake when they imprisoned those writers, Sinyavsky and Daniel." (7)

It was a serious political mistake, because, it gave the opportunity to dissidents, through the December 5th demonstration, to advance a demand that was impossible for Soviet authorities to openly deny: the demand to observe their own Soviet law. In opposing this demand, the Soviet regime would not be confronting only the few vocal dissidents in Pushkin square — it would be pitting itself against the incomparably more, who understood that the law was their only protection from arbitrary persecution.

It was the realization that the Legality Program hid a well crafted and very dangerous political trap, that lead to the very hesitant initial official reaction to the dissident challenge. This, in turn, proved that Soviet authorities were not willing, yet, to launch a campaign of violent repression, in the Stalinist spirit. And this was the true victory of the Pushkin Square. With it came the realization that dissidents had an effective political tool which the Soviet regime could not easily defeat. After that, dissent gained momentum:

"That (the demonstration) produced some impression. And then other people did require the same [publicity] with letters, petitions and so on. It is interesting that I [had] tried in each occasional arrest just to prevent the lack of publicity. To demand the publicity. After [the demonstration], we got it."

Yessenin-Volpin's Legality Program had given the loose group of people that were opposing the Soviet regime with isolated and sporadic acts of personal disobedience, a common denominator — and with this, it had converted the scattered individual dissidents to a cohesive political movement. The movement also attracted an unimpeachable leadership: Andrei Sakharov, the creator of the Soviet hydrogen bomb, also added his voice:

".... The last two years, a year and a half, I met [with Valeri]] Chalidze, who wrote that Man must receive human rights. Sakharov also was invited. I met with Sakharov and about a year and a half, we met ..., we discussed ... these problems. There was a magazine 'Social Problems.' Before that, in 68, [Sakharov] had published in samizdat, a paper about 'Reflections [on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom.]' I read ... that but I did not know about his larger activities. Chalidze and Tverdokhlebov had organized that (the meeting with Sakharov) and he came to us ... I met him in November25, (1970.)"

Suddenly, the Soviet regime was confronting something it had never faced before: A political opposition that was using sophisticated political methods, had well defined tactical goals, and had attracted a true Soviet icon to its leadership. This constituted an unprecedented crisis for the Soviet system, which the regime solved by the only way possible, under the social circumstances of the era. As Yessenin-Volpin remembers:

"... that [the power of the Legality Program] was understood and actually, maybe the first time, authorities tried to prosecute — but it was too late. Everyone was against them. And that is why they actually decided to let the emigrants go. ... I left Russia — I thought forever. I could not, of course, think otherwise.I left in May 31, 72."

Not, though, without a final application of the Legality Program. As Vladimir Bukovsky writes:

"... only Volpin leaned out of the train that took him to Vienna and made a speech on the need to struggle for the right of re-entry."(8)

If Soviet authorities had hoped that Yessenin-Volpin's expulsion-emigration to the West, would neutralize his ctiticism and brake his independent spirit, they had, again, miscalculated. His intellectual work had already changed the very nature of Soviet political life — a fact that became blindingly obvious when, a few years later, the General Secretary of the Communist Party started suddenly demanding "Glasnost," himself. And Yessenin-Volpin did not stop even for a moment working on his philosophical and political ideas, often with considerable success. In 1972 he published the important article "On the Logic of the Moral Sciences" in which he explained his ideas on the application of Logic in the social functioning. He also continued contibuting to his chosen professional field, Mathematical Logic — in fact, some of his later works are considered fundamental in the subjects they treat. He taught at Boston University for a few years and gave numerous seminars on his work and ideas in many Universities. But he believes that his greatest work is still in the future. He is, now, polishing a major text on the foundation of Mathematics, with which he is attempting to repair the fundamental problem in the structure of the discipline that the Gödels paradox creates. For many traditional mathematicians this is a utopian dream: Things are what they are, and, sometimes, one should just accept that it is futile to try to change them.

But, history has shown that Yessenin-Volpin has a habit of proving such a pessimism wrong.

|

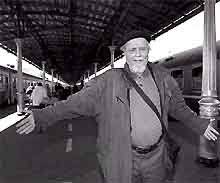

Alexander Yessenin-Volpin back in Moscow, in 2002! |

Part 2: Cybernetics vs. Historical Materialism: The Legality Program and the Dissident Movement.

Notes:

(1) All excerpts in this part — except when noted otherwise — are from an interview Alexander Yessenin-Volpin gave to the author on September 20, 2002, in Boston. text

(2) Alexander Yessenin-Volpin A Leaf of Spring (New York : Frederick A. Praeger Publisher, 1961.) text

(3) Leon Trotsky To The Memory of Sergei Essenin. Written: January 1926 Publisher: Pravda Source: Fourth International, No. 4, Autumn 1958. Online Version: Marxists Internet Archive, 2000. Transcribed: Sally Ryan. HTML Markup: Sally Ryan and David Walters. http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/1926/1926-essenin.htm text

(4) Alexander Gribanov http://www.brandeis.edu/departments/sakharov/Exhibit/faces.html. text

(5) Vladimir Bukovsky, To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter (New York : The Viking Press,1977.) p. 194. text

(6) Peter Yakir, son of revolutionary commander Yona Yakir text

(7) Interview with Alexander Yessenin-Volpin November 15, 2002. text

(8) Vladimir Bukovsky To Build a Castle, p. 241. text

In the spelling of Yessenin-Volpin's name I followed his own preference. I retained, though, the traditional spelling for the name of Sergei Esenin.

The photographs and images above come from different sources. Their copyright remains with their owners. Please e-mail us for information about who should be contacted for a permission for use.